By Rita Ho

When the average person hears that I’m the designer on the Growth team for Wikipedia, there’s a common misconception that it’s about growing the number of readers, the more commonly thought of “Wikipedia user”. However, our team was formed almost three years ago with a different challenge and audience as our focus. This article aims to tell the six-part story of how and why we started this team, and all the failures, learnings, and successes we’ve had since.

- Identify the problem

- Plant the seeds for Growth: Research

- The set up: Team process & principles

- Design experiments 1, 2, and 3: Down, up, and up

- Now what? Doubling down and scaling up

- What’s next

1. Identify the problem

While it’s commonly known that Wikipedia is a multilingual project, one thing that may be surprising is how much variation there is between articles on the same topic in different languages. For example, the French canelé article has a fairly different history on the origins for the small pastries than its English version[1]. This is because each article version is written by its own community of editors, not machine translated[2]. The diversity and breadth of content across around 300 languages is awesome, but it also presents a challenge:

How might we grow knowledge across all languages?

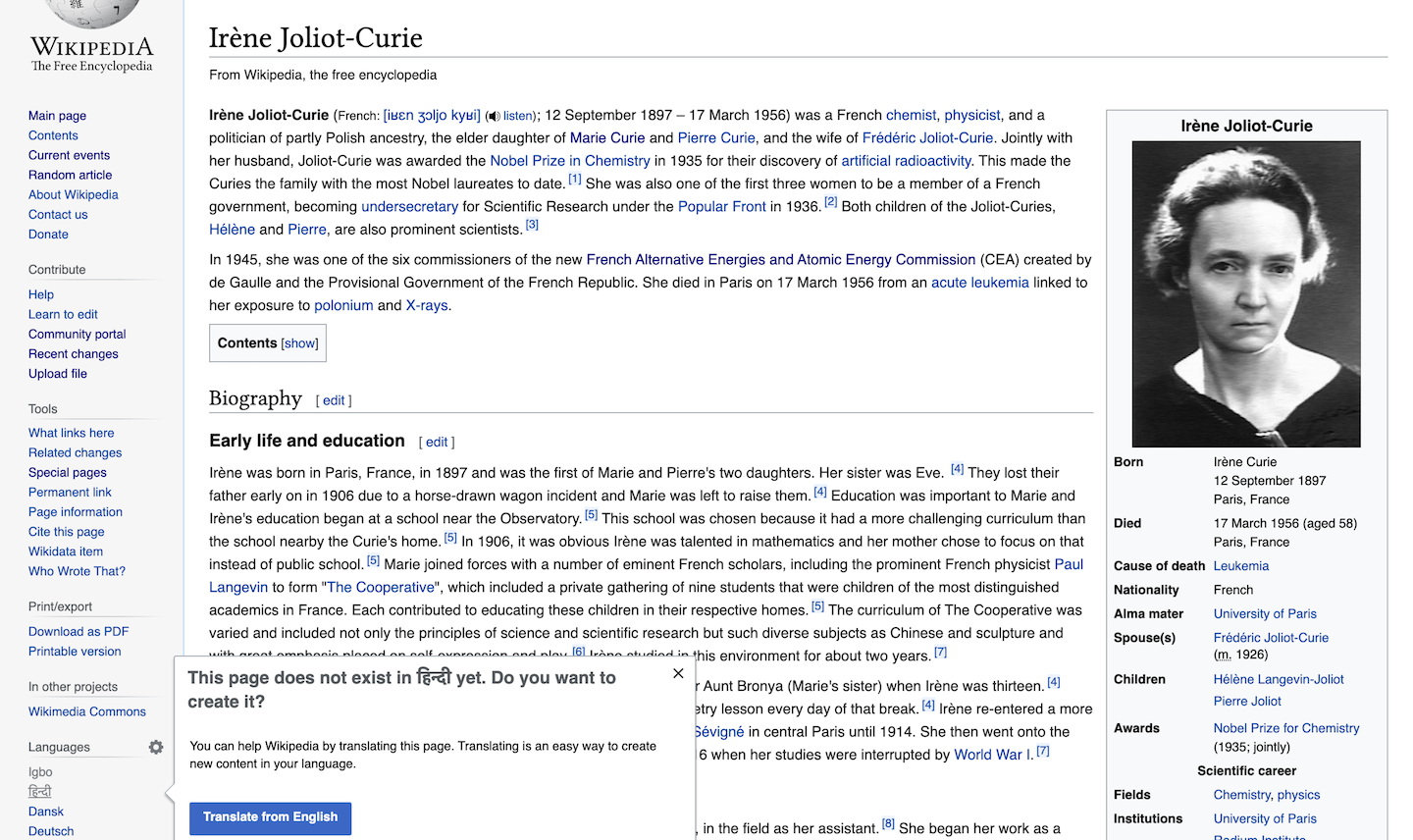

Currently the largest Wikipedia language is English, with ~6.3 million articles[3]. Contrast this with the Hindi version (the 4th most spoken first-language, just behind English[4]) with ~147K articles[5]. This highlights the many knowledge gaps that exist on Wikipedia – and how it is a massive barrier to information access for those who don’t know English. To continue on the case of the canelé, (as of writing) there is no article about the deliciously rich heritage of these pastries documented on Hindi Wikipedia at all. Or to give a more ‘serious’ example of the knowledge gap (though one would argue pastries are a culturally significant item), the Hindi edition also lacks biographies for prominent figures like Nobel laureate Irène Joliot-Curie, or conservationist Dian Fossey.

The Wikimedia Foundation’s vision is to ensure that every single human being can freely share in the world’s knowledge, which can only be accomplished if more people contribute to that corpus of knowledge across all languages. Unfortunately Wikipedia has seen the number of contributors (a.k.a. editors) either stagnate or shrink over the years, and struggle to attract and retain new folks. A notable metric is that around 94% of first time editors don’t ever stick around to make a second edit[6]. The Growth team was formed at the Wikimedia Foundation in July 2018 to directly address this problem. There need to be significant increases in the number of contributors as well as a more diverse contributor pool in order to supply knowledge that is relevant to everyone in the world.

With this in mind, the Growth team’s objective is to:

- Increase contributor activation (people who make a first edit)

- Increase contributor retention (people who come back another day to make subsequent edits)

We have also concentrated on working with smaller-to-medium sized Wikipedias to help promote the diversity of the contributors (rather than the larger, established language Wikipedias who tend to be an established homogenous group).

2. Planting the seeds for Growth: Research

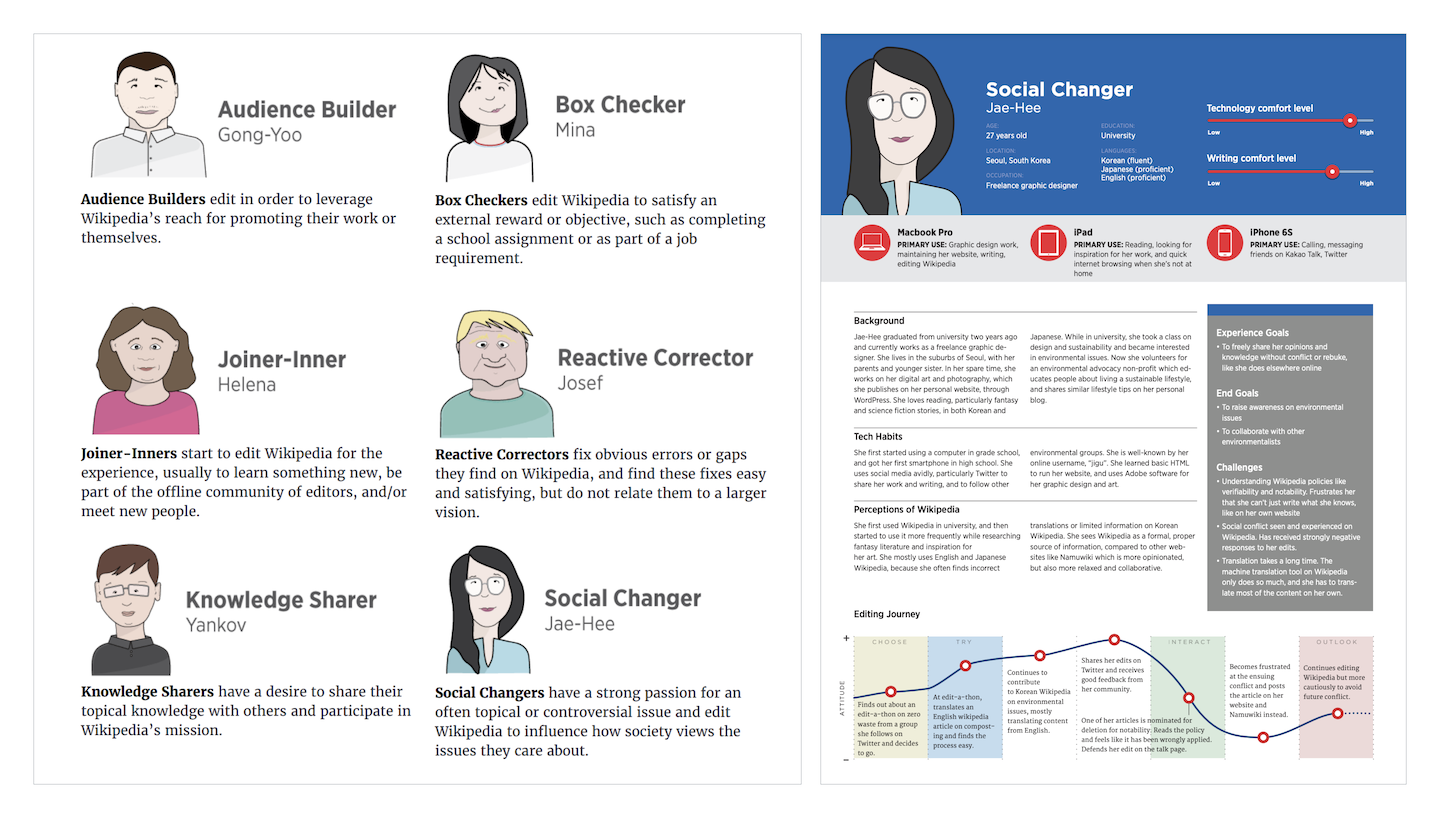

The inception of our work actually began a year earlier with the “New Editor Experiences” research project in 2017. This was a foundational research project aimed at learning as much as possible about new editors in Korean and Czech Wikipedias – two languages chosen as representative of many smaller Wikipedias. The project was conducted not only in collaboration with a research partner Reboot, but also with Wikipedians in Korea and Czech, with a “Community ambassador” role created for a long-term active member in each language, to encourage their communities’ participation in the project. In all, 64 interviews were conducted in Korea and Czechia to draw out a number of important insights about new editors.

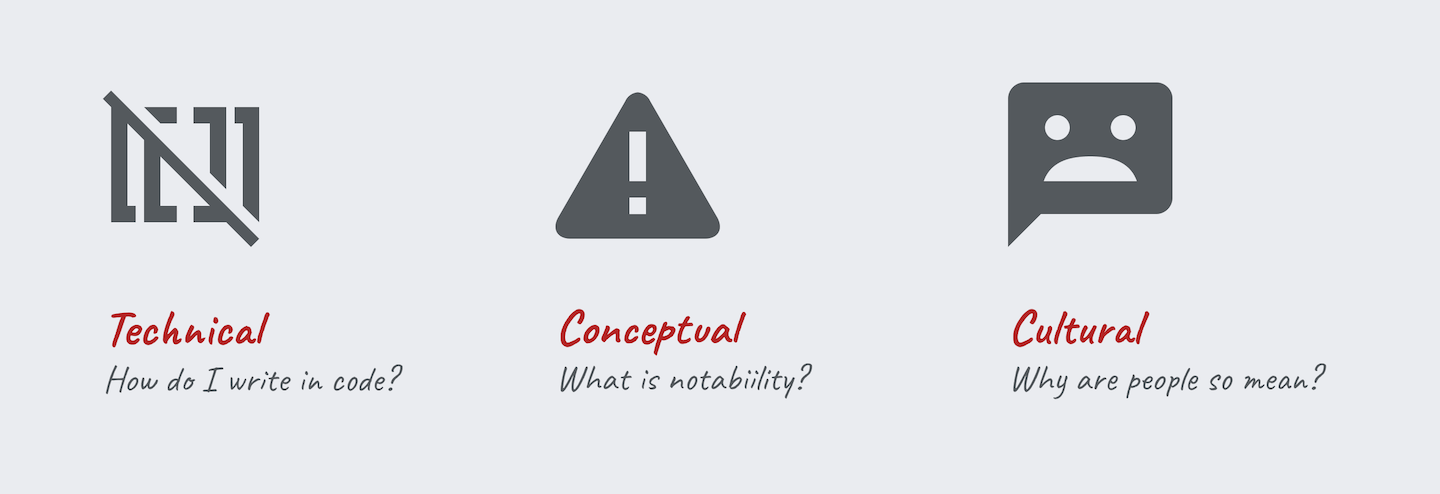

One of the outcomes of the research was identifying that contributors have very different motivations for editing (represented in the personas). Despite their differences, all these newcomer personas encountered one or more of these key barriers to editing:

- Technical barrier (e.g. How do I write in code?) – Newcomers have trouble finding and using editing tools. A lot of our editing tools can seem too overwhelmingly open-ended and complex for them to know where to even start.

- Conceptual barrier (e.g. What is “notability”?) – How do they write the “Wikipedia way”? What does it mean when their subject is not notable enough? What is NPOV?

- Cultural (e.g. Why are people so mean?) – Newcomers are often unaware of the collaborative effort involved in writing Wikipedia. In turn, they can’t easily become part of the “community” of established and active editors, because they don’t know it exists. And for many, their first interaction is not positive because it’s someone telling them they did something wrong, or reverting their edit.

Besides the different newcomer needs, motivations, and challenges being surfaced, the research concluded with a number of recommendations. This was where the Growth team came into the picture, as it was formed to take action on these recommendations.

Our aim was to experiment with design interventions to drive increases in activation and retention of newcomers.

3. The set up: Team process and principles

Vanilla Ice once sang, “Stop, collaborate and listen”. Our team works according to similar principles, but in a different order.

1. Collaborate in the open

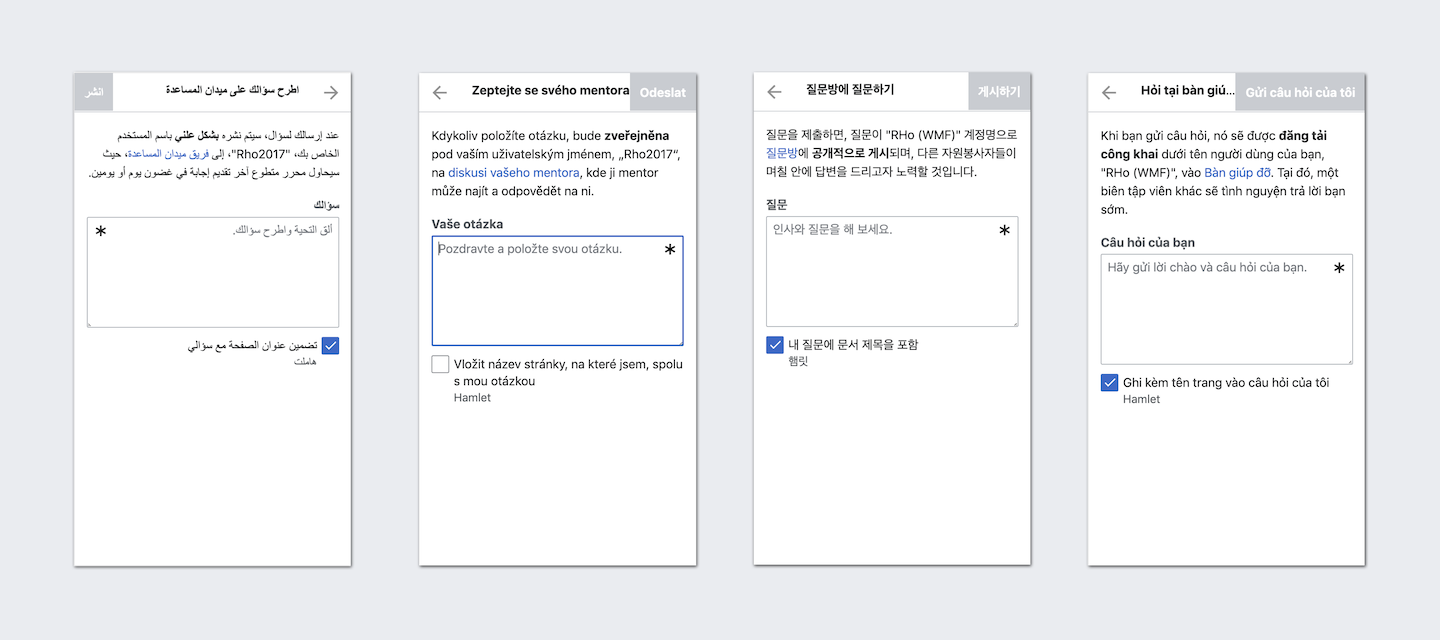

Modelling on the success of the New Editor Experiences research approach, a core part of our process is to ensure close communication and collaboration with the communities in which we work. The first thing we did when the team was formed was to partner with four “pilot” languages (Korean, Czech, Arabic, and Vietnamese) that we would collaborate with in controlled experiments. In addition to the team’s Community Relations Specialist (a liaison between Wikimedia product teams and volunteer community members), we created a “Community Ambassador” role for each pilot language – a representative who helps us to collaborate with their respective members on a range of tasks such as translation, communicating our progress, and recruiting others to participate in our project.

Notably, not only do we collaborate with our communities, but because it’s Wikipedia – anyone can be a part of the community – so we work in the public. We post in-progress designs and engineering updates that anyone interested can react to and give feedback.

2. Listen

We listen to all the feedback coming back on our work, from usability testing on early stage designs through to analysing data from our released experiments in order to decide how to improve. We also listen to our community partners, and try to ensure there is sufficient flexibility and adaptability in designs to work for different groups.

3. Stop (if it’s not working)

A very important work principle we try to keep in mind is that experiments fail. When we see something is not working, we try to make a clean stop and take learnings from that failure to make the next experiment better.

Of course, nested in this last principle is making sure we are measuring results rigorously, and running controlled experiments for everything we try.

4. Design experiments 1, 2, and 3: Down, up, and up

To illustrate our process and journey, I’d like to talk about three key experiments our team has worked on based on major recommendations from the design research.

#1 Help panel: A helpful failure

One of our first experiments was based on research recommendations for better in-context help (small doses of help relevant to the activity being done at that moment), as well as human-to-human help (providing a real connection to a friendly person in the community). In a nutshell, the feature was a help panel tool available to newcomers when they opened an article for editing, and allowed them to search and/or ask questions to experienced users about how to edit.

In order for this design to work in practice, not only did we consult with all our pilot wikis for buy-in on the idea, via our ambassadors, but we needed these very experienced editors from each language to sign up to answer questions. So community engagement was doubly important for this experiment.

The engagement with the help panel was quite high[7] considering its ancillary placement and function, so we considered it a positive sign that newcomers want in-context and human help. An interesting tidbit was that there were cultural differences in the usage, where Koreans asked very few questions compared to the other pilot wikis. However, per our “Stop if it’s not working” principle, we ultimately didn’t see any change in more people starting to edit or being retained, so we paused further iteration and went to try a different idea.

#2 Newcomer homepage: A welcoming place

The Newcomer homepage was the second project built as a result of the usability testing of our earlier work, where we noticed a lot of test participants expected a dashboard or some homepage to orient themselves.

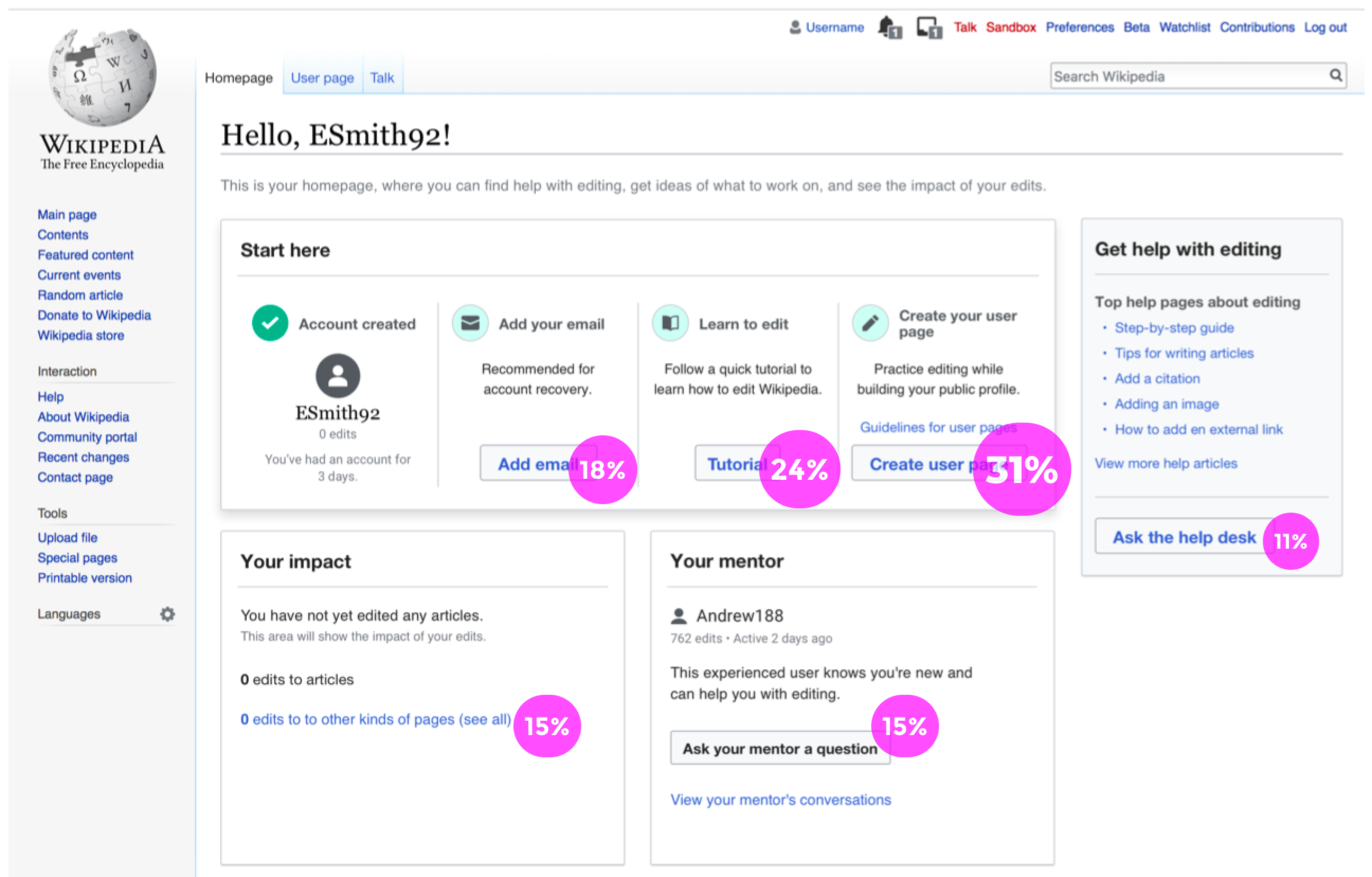

So we created this “newcomer homepage” that gives them that clear place to start.

In its first iteration, it contained a few different modules that help someone learn about editing, encourage them to create a user page, and seek help from both the help desk or from a specific experienced editor assigned as their mentor.

It was encouraging to see people engaging with this page and returning to it on multiple days to take different actions. One of our most important observations was that the most popular button was for creating a “user page”, which is like a user profile in which newcomers can identify themselves to others. The engagement with this button gave us a very strong signal that newcomers will start contributing if given a call-to-action.

#3 Newcomer tasks: Suggestions to get started

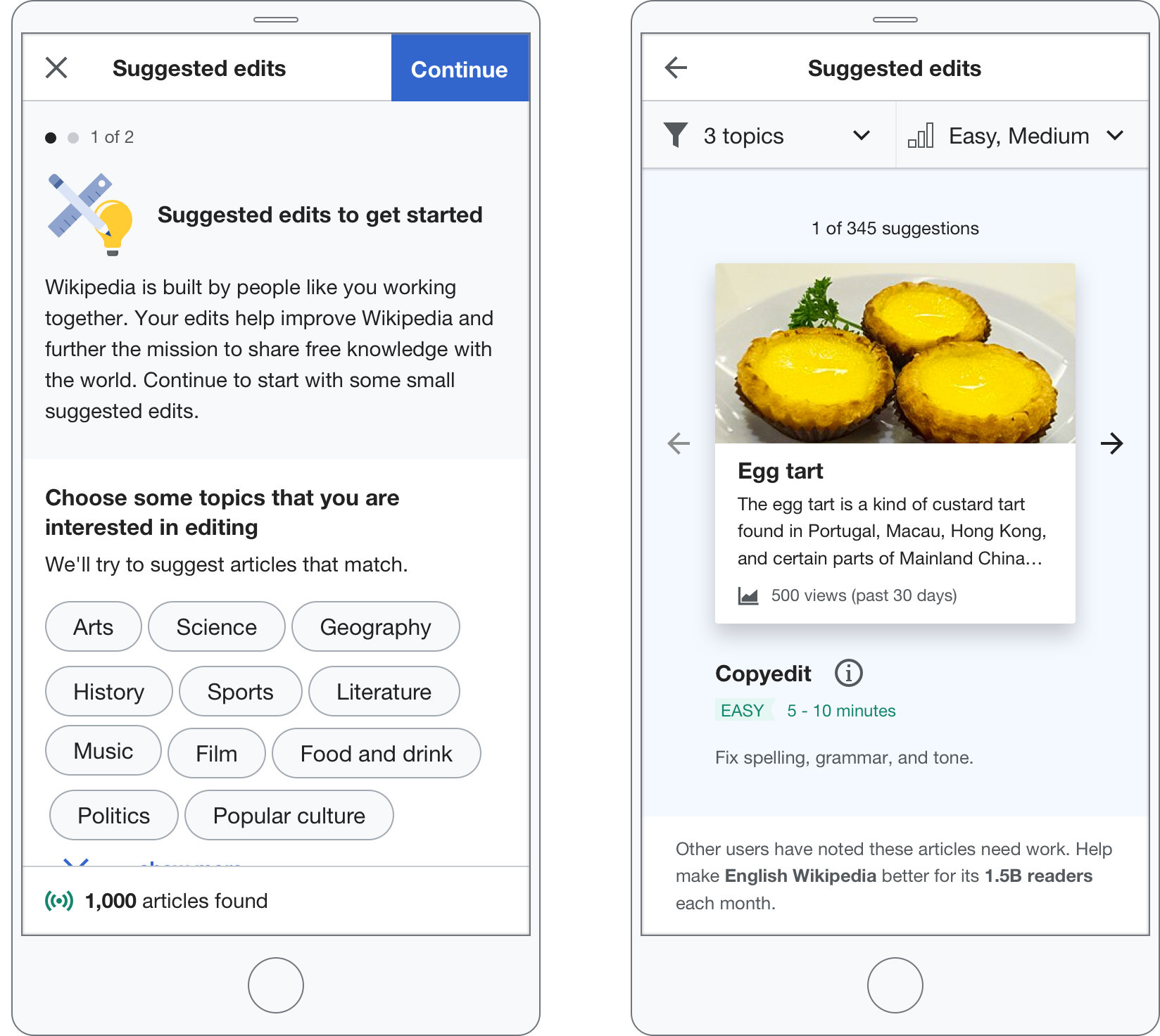

A natural next step after seeing newcomers interacting and seeking out editing actions on the newcomer homepage was to give them opportunities to edit actual Wikipedia articles. We did this in the form of newcomer task recommendations, a feature we call “Suggested edits” on the homepage.

Based on foundational research and cumulative feedback from previous experiments, we knew that many newcomers either arrive with a very challenging edit in mind (e.g., write a new article from scratch) from which failure becomes a demoralising dead-end, or else they don’t have any edits in mind at all, and never find their footing as contributors. The “Suggested edits” module offers tasks ranging from easy tasks (like copyediting or adding links), to harder tasks (like adding citations or expanding articles) that newcomers can filter to based on their specific interests (e.g., copyedit articles about “Food and drink”). This feature is intended to cater to both groups – a clear way to start editing for those who don’t know what they want to do, and for those who do have a difficult edit in mind, it provides a learning pathway to build up their skills first.

Since its launch, and as we added more editing guidance and improvements to the homepage design over multiple iterations and variant tests (a subject for another post), we’ve seen steady increases in edits and number of editors using it. In other words, the release of this experimental feature saw us succeed in increasing editor activation and retention. 🙌 🙌

5. Now what? Doubling down and scaling up

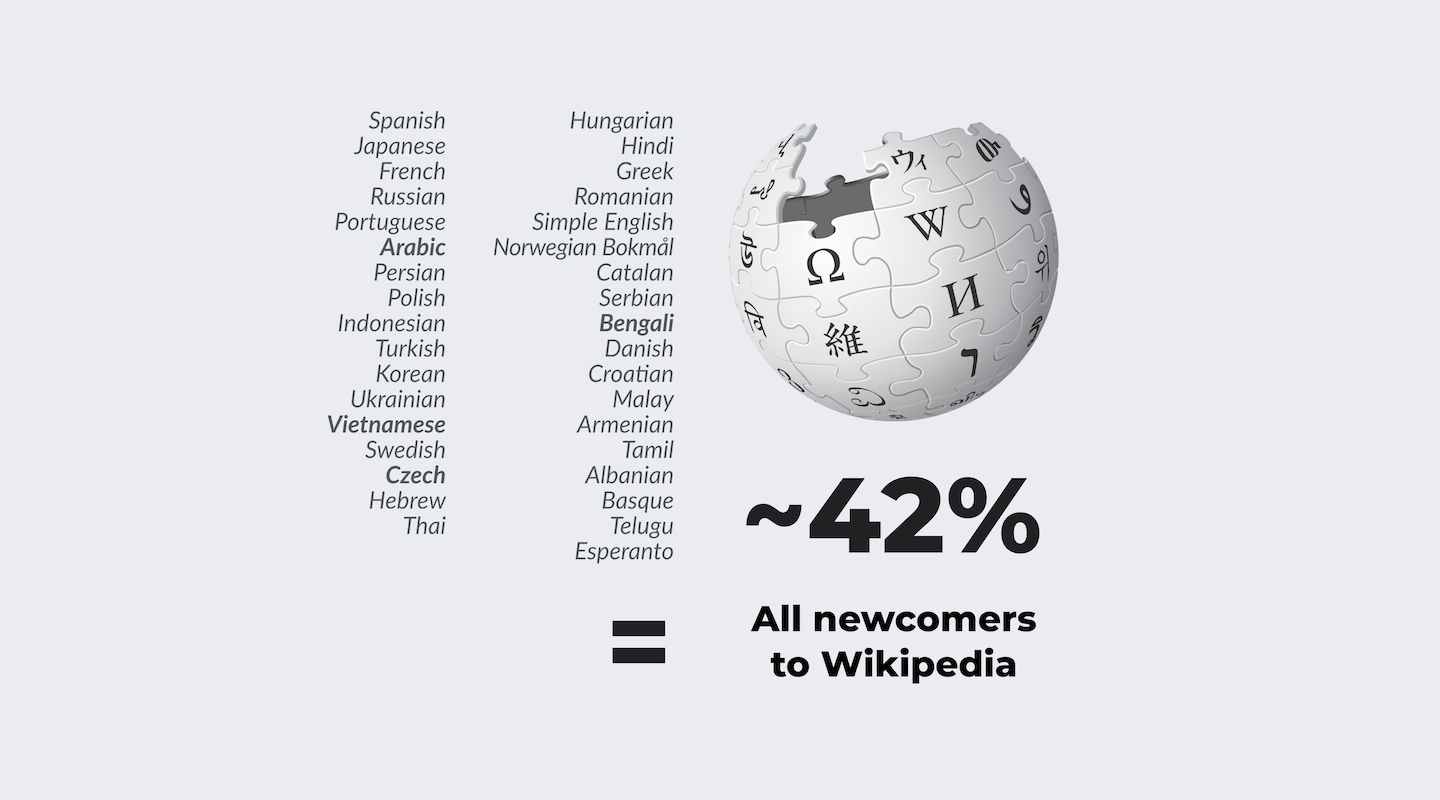

The success we saw in the pilot languages meant that we are able to work on the next great problem to solve: how can we scale up and encourage all the other Wikipedias to adopt our features?[8] Luckily, one of the benefits of working in this somewhat slow-and-steady approach is that as the team consults with the different language communities, we’ve got a lot of supporting data and built up a lot of trust from collaborating with our pilot communities which has helped encourage many language communities to sign up. To date, we’ve added the features to 35 Wikipedias, which, when accounting for the relative sizes of the languages, amounting to nearly half (42% to be exact) of all newcomers to Wikipedia.

Reflecting on the time it has taken from the initial failed experiment with the help panel to the modest success we’ve had so far in increasing new contributors, these were my biggest realisations about what it is to design with and for the open community of communities that is Wikipedia.

- Importance of collaborating with communities for adoption & understanding. Collaborating with our communities is paramount for trust, acceptance, and improved user experience

- Experimenting with an open mind (and being ready to fail with a next plan).

- There’s no one size fits all for everyone. Accepting that actually, there is no perfect design for everyone. Seeing how different cultures and languages react to and use the same design differently has made me realise the importance of allowing a degree of customization, to empower different communities to figure out what’s best for them.

- Change takes time and perseverance.

6. What’s next?

We’ve now established a good cadence to our experiment-and-scale-up-on-success approach, and as the Growth team features become available on more Wikipedias, our ultimate goal is that one day these will no longer be experiments but a core part of welcoming editors to the Wikipedia community. So, mission accomplished right?

Thankfully, my job as a designer is not done here.

You may have noticed that all the design interventions so far have been about trying to get newcomers to succeed by giving them access to help and suggestions to edit using the existing editing interface. At the moment, if someone selects a suggested edit to “copy edit” an article, they don’t receive any specific pointers about what part of the article needs help with fixing spelling or grammar. Our newcomers still need to know which of the many editing tools they should be using, and will often need to ask for more guidance. And that’s what instigated our team’s latest design exploration: Structured tasks.

The idea is that instead of guiding people through the current complex, open-ended editing UI, we create new, easier ways to edit. And we will do this by breaking down editing tasks you can do on Wikipedia into a series of single smaller steps or “structured tasks” instead. Something that newcomers can quickly and easily accomplish.

The very first structured task that we have designed is to review suggestions by an algorithm to make words in a Wikipedia article link to other articles, and we are again approaching this by seeing how this new task type is working firstly for our pilot Wikipedias by the start of June 2021. I’m anxiously optimistic about how this next experiment goes, fodder for another post, but until then (and until there’s time for another blog post), you can learn more about our work on our team page.

Cover image by Rizzelli Stefania. Taken from Commons, licensed under CC-BY-SA-4.0.

Thanks Marshall Miller, Jessica Klein, and Margeigh Novotny for your feedback and editing help.